How to Cycle Sync Your Strength Training Workouts to Build and Maintain Lean Muscle

Applying the progressive overload principle throughout your menstrual cycle for better results.

This article explores the progressive overload principle in a strength training context for the purposes of increasing and maintaining muscle mass for menstruating women.

A Case for More Muscle

The wide-ranging benefits of building muscle—especially for women—are no secret. However, they bear repeating as we make the case for strategic strength training with your cycle.

Increased muscle mass has been shown to:

Improve insulin sensitivity for better metabolic health [1]

Increase energy demand and burn more calories [2]

Delay the onset of age-related dysfunction [3]

Help prevent injury and increase functional strength [4]

Slow bone loss and improve heart health [5,6]

Promote immune function [7]

When applied thoughtfully and with your cycle in mind, strength training promises an upgrade in your overall health while improving energy and muscle mass.

What Is Progressive Overload?

Progressive overload involves gradually increasing an exercise stimulus beyond what your body has previously adapted to in order to build strength, endurance, and new muscle tissue (see examples below). While the progressive overload principle can be applied to any form of exercise, this article focuses on resistance training.

Resistance training for sustainable body composition change—namely fat loss and muscle gain—is about the long game. You may not see immediate results in one or two sessions, but instead you’ll experience incremental changes that accumulate over time.

The term “progressive” defines this important strength training principle because the application happens over an extended period. A good rule of thumb is to “progress” the stimulus by no more than 10–20% each week depending on your starting range and fitness level.

Methods of Progressive Overload

There are a number of different ways to progressively overload a given exercise and for measurable results, it can be helpful to focus on pulling only one lever at a time.

Resistance: increase the load (weight) moved during the exercise

Reps: increase the number of repetitions performed

Duration/Volume: increase the number of sets performed

Intensity: increase the tempo of a given exercise for a greater rate of perceived exertion

Frequency: increase the number of training sessions in a given period

Movement Mastery

To safely apply the progressive overload principle, it is important to master the mechanics of each movement pattern before adding load. This means performing bodyweight repetitions with impeccable technique before increasing weight or reps. After you begin loading an exercise and as the load and/or repetitions increase, form remains paramount to prevent injury.

Muscle-Protein Synthesis

In order for the progressive overload principle to be effective, we must support the body’s system of muscle-protein synthesis. This process of building new muscle tissue requires that you have three key elements in motion.

Stimulus. You must produce a stimulus during workouts that exceeds existing thresholds to produce positive stress/damage. (These are your workouts.)

Materials. You must deliver protein building blocks containing essential amino acids to support the synthesis of new muscle tissue and mitigate muscle breakdown. (This is your nutrition.)

Adaptation. You must allow sufficient time for muscles to repair between sessions. The metabolic response to an exercise stimulus lasts about 24–48 hours. (These are your rest days.)

Cycle Syncing the Progressive Overload Principle

This training principle is generally implemented over periods of 6–8 weeks. However, in naturally cycling women, the timing of the overload stimulus matters.

For instance, if you continue increasing intensity and volume at the same rate through your high-hormone phase (luteal phase), a progressive overload protocol could have detrimental effects like muscle loss when your metabolism is inherently catabolic (breaking down tissues).

Below is a high-level overview of a phasic approach to progressive overload that accounts for the key metabolic shifts that occur during each menstrual cycle.

New to syncing your fitness with your cycle phases? Check out the on-demand lunae collective membership for access to hundreds of phasic workouts for just $14.99/month!

Low-Hormone Phase: Early Follicular

estrogen ↓ progesterone ↓

The late menstrual and early follicular phases are marked by low hormones which promote quicker recovery times, better carbohydrate utilization, and more efficient cooling. This low-hormone phase is a great time to begin a progressive overload protocol—generally around cycle day 3 or 4 when energy levels return after your heaviest flow.

Think of the time between your period and ovulation as a performance window where you can exert more energy with less consequence.

Week 1

Set the first week of your cycle as a baseline effort from which you will progressively overload. This is your starting point for reps, weight, volume, etc.

Each exercise performed should demand a considerable effort where you feel a challenge in the last few reps of each set and as always, allow 24–48 hours for a given muscle group to recover.

Sample Lower Body Workout |

||||

| Exercise | Weight | Reps | Sets | Rest |

| DB front squat | 20lb x 2 | 10 | 4 | 90s |

| DB deadlift | 20lb x 2 | 10 | 4 | 90s |

| side lunge (L/R) | 20lb x 2 | 10 | 4 | 90s |

| curtsey lunge (L/R) | 20lb x 2 | 10 | 4 | 90s |

| prone hamstring curl | 20lb | 10 | 4 | 90s |

Week 2

Start building momentum in the second week of your cycle when hormones are still relatively low and trending toward elevated estrogen which promotes anabolic (building) metabolism.

As you repeat the baseline workout from week 1, you might increase the reps from 10 to 12, add 1-2 lb to your dumbbell weight, or perform an additional set.

Mid-Cycle: Late Follicular and Ovulatory

estrogen ↑ progesterone ↓

As you approach mid-cycle, the estrogenic transition boosts energy levels and muscle-building potential with a surge in anabolic hormones.

You may also notice that despite more energy overall, high-intensity efforts feel tough. This is because estrogen flips a metabolic switch where your body starts to favor fatty acids for fuel over carbohydrates. This energy substrate takes a little longer to get going, but shouldn’t hold you back. Approach the transition from week 2 to week 3 with your peak effort.

Week 3

In the sample workout above, you might add a timed element to overload via tempo—aiming to beat your week 2 reps using a 40/20 interval structure for each exercise.

Another option would be to bump up your reps to 15 or keep the reps the same as week 2 and add another set.

As described above, the easiest way to track your progress is to focus on overloading one element at a time. Establish your baseline conditions for a particular exercise (weight, reps, volume, and rest) and then increase in equal increments for the first 3 weeks.

High-Hormone Phase: Luteal

estrogen ↑ progesterone ↑

Naturally cycling women can generally get away with a lot in the first half of the cycle—high intensity efforts, heavier weights, shorter recovery periods. However, the second half is when the real work of cycle syncing begins.

Think of the time between ovulation and your next period as a preservation window where the strength training strategy changes from building to preserving hard-earned muscle.

After the estrogen surge during the ovulatory phase, we typically see a brief dip in hormone levels. For some, this can produce similar effects to PMS as the body adjusts to the sharp decline. However, these few low hormone days are generally a safe time to proceed with strength training efforts while gradually dialing down the intensity.

Week 4

Approach the start of this week with a maintenance mindset.

With your metabolism trending toward catabolic, any excess exertion can lead to muscle tissue breakdown and fat storage.

A traditional progressive overload protocol would continue incrementally adding to the exercise stimulus week by week, but a cycle-friendly approach does the opposite in the luteal phase.

In the workout example provided above, you might shift to more of an endurance effort where you’re moving through each exercise for more reps with less weight—10 lb for 20 reps as an example. Another approach would be to slow the tempo down and change the loading pattern, again with lighter weights. You might even eliminate the weights altogether and perform a deloaded version of the workout.

In contrast to conventional fitness programming, low-intensity efforts will provide the highest return in high-hormone territory. Give yourself permission to continue challenging, but sustainable work that doesn’t feel depleting. And give yourself more recovery time between sessions in the luteal phase when resources are limited and your body’s mission is to build the endometrium, not muscle.

What Happens Next?

As described above, the progressive overload principle is typically applied over a period much longer than a single menstrual cycle. You might be wondering how to move forward after turning down the intensity in the luteal phase.

Celebrate and Course Correct

Celebrate your progress with the completion of a full cycle. Acknowledge your hard work and allow space for reflecting on the previous month’s workouts. i.e. What worked well? What felt forced? What are you most proud of? What are you excited about working on next month?

As you enter a new cycle, make any course corrections necessary to support your goals, schedule, and upcoming commitments. For instance, do you need to change the frequency of your workouts or the duration? What equipment might you consider to support further progress?

Pull A New Lever

Depending on how you approached the last completed cycle of overload, you may consider pulling a different lever to continue making progress. For instance, if you worked primarily with incremental reps in a specific exercise or workout, consider adding incremental weight to your baseline and completing another round with a similar rep structure.

On the other hand, if you were gradually increasing weight in each week, you might shift toward adding a rep or two to each set while keeping the weight the same.

The Continuum of Progress

As you explore the principle of overload, you will begin to notice gradual adaptations with each new cycle—especially if this is a new approach to your training. What once felt challenging starts to become more manageable and it takes a new progression to continue shifting your edge and avoid plateaus.

In an active lifestyle where strength training is part of your regular practice, progress lives on a continuum and over time, the change becomes less linear and more nuanced.

You may have to get creative when you hit a ‘max’ working effort in a particular exercise, changing things like the range of motion, tempo, rest interval, power, etc. You may shift into more of a maintenance mode and focus on overloading a single exercise at a time rather than an entire workout.

Using this principle in alignment with your cycle gives you more runway to work with because you’re effectively getting a reset during each luteal phase. With a week or so of low-intensity and recovery efforts, you can come back in and start fresh in each new cycle!

Ready to Get Started? Here’s a Phasic Progressive Overload Series

If you’re new to strength training or in the early stages of syncing workouts to your cycle, it can be challenging to create a realistic progressive overload plan that moves you toward your goals and keeps your hormones happy.

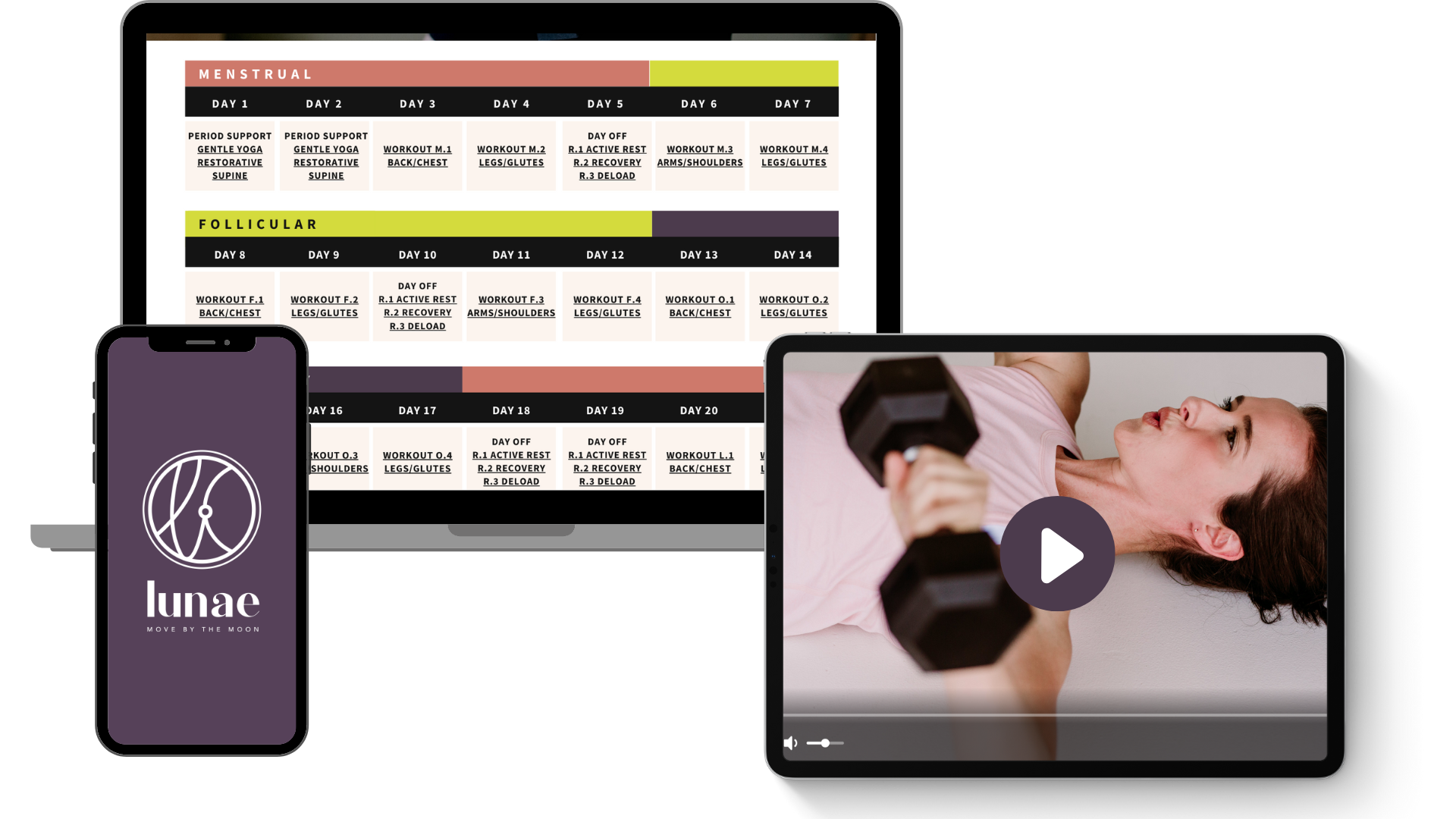

In the lunae roadmap of exercise, you can explore a complete cycle of progressive overload workouts that will guide you every step of the way. This strength training series includes:

A comprehensive workout journal with calendars, workout logs, and additional support to keep you on track.

Movement tutorials, warm-ups, and cool-downs in each workout.

(16) guided workouts—four split sessions in each phase.

(10) additional guided movement practices for your period, PMS support, and recovery.

Let’s get stronger together and move by the moon!

Srikanthan, P., & Karlamangla, A. S. (2011). Relative muscle mass is inversely associated with insulin resistance and prediabetes. Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 96(9), 2898–2903. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-0435

Aristizabal, J., Freidenreich, D., Volk, B. et al. Effect of resistance training on resting metabolic rate and its estimation by a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry metabolic map. Eur J Clin Nutr 69, 831–836 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.216

Srikanthan, P., & Karlamangla, A. S. (2014). Muscle mass index as a predictor of longevity in older adults. The American journal of medicine, 127(6), 547–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.02.007

Fleck, S. J., & Falkel, J. E. (1986). Value of resistance training for the reduction of sports injuries. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 3(1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-198603010-00006

Hong, A. R., & Kim, S. W. (2018). Effects of Resistance Exercise on Bone Health. Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea), 33(4), 435–444. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2018.33.4.435

Srikanthan, P., Horwich, T. B., & Tseng, C. H. (2016). Relation of Muscle Mass and Fat Mass to Cardiovascular Disease Mortality. The American journal of cardiology, 117(8), 1355–1360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.01.033

McLane, L. M., Abdel-Hakeem, M. S., & Wherry, E. J. (2019). CD8 T Cell Exhaustion During Chronic Viral Infection and Cancer. Annual review of immunology, 37, 457–495. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055318